Archival Discussion

| Although he keeps in close personal touch with the affairs of the farm by telephone and visit, Mr. Harris employs a superintendent, who is paid to board and is in charge of the laborers required. |

With a total farm labor cost of $1,860.92 for 1910, the superintendent's salary must have been quite modest. The families of superintendents and farm managers continued to occupy the building through the 1960s.

Site Description

|

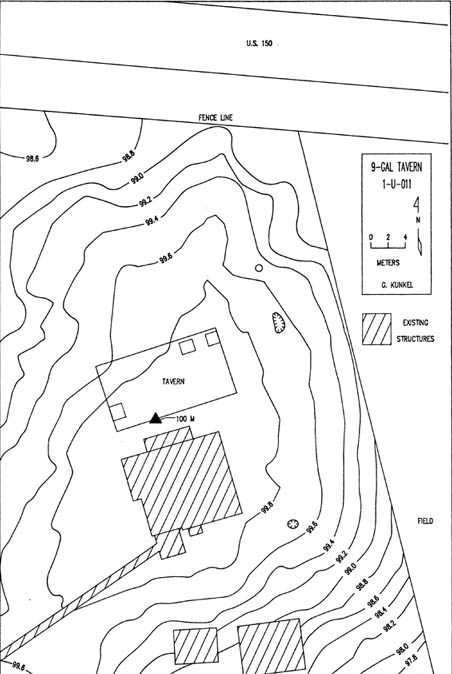

| Figure 1. The Nine Gal Tavern Site. |

Research Design and Data Collection

- Q1: Was there a residential structure at this location after 1834?

- Q2: What was the chronology of occupation?

- Q3: What was the site function and did it vary over time?

- Q4: Is there evidence of different tavern forms?

1. An examination of the interior of the existing house and out-buildings. Of particular interest were exposed structural elements. The goal was to identify materials salvaged from the Bryan constructions.

2. Surface collection of large tracts of the farm. Eighty acres stood as relict timber. All of this tract, as well as some cultivated ground was undergoing development as an upper class subdivision by the fall of 1986. The main drainage ways were being reorganized for the construction of two flood control impoundments. Exploiting these disturbances, every exposed patch of earth was examined. Consequently, much of the land surface that had supported forest and savanna was accessed. From the beginning of the survey, the ground that had supported prairie revealed extremely low densities of human detritus; consequently, it received less attention.

3. A systematic shovel probe survey of the house site was conducted. The survey was accomplished using a grid based upon 2 m centers. At each grid intersect a shovel probe 30 cm in diameter was excavated to culturally sterile soil. The grid was anchored at site datum. The shovel probe grid extended beyond the limits of the primary residential scatter.

4. The north-south and east-west lines of the grid were swept with a metal detector. Where readings indicative of a metallic object were encountered, a shovel probe was excavated.

5. To acquire information about what might lie beneath the existing structure, two 1 m by 2 m test units were excavated. The units were positioned parallel to the foundation walls and on either side of the front door. The units were dug to sterile soil.

6. Where subsurface features were encountered test trenches were excavated to sterile soil. They were 30 cm wide and extended beyond the limits of the feature.

Findings

1. Excavations and feature descriptions:

|

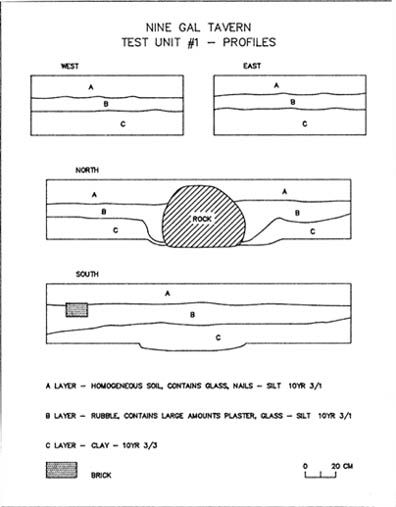

| Figure 2. Test Unit #1 of the Nine Gal Tavern Site. |

|

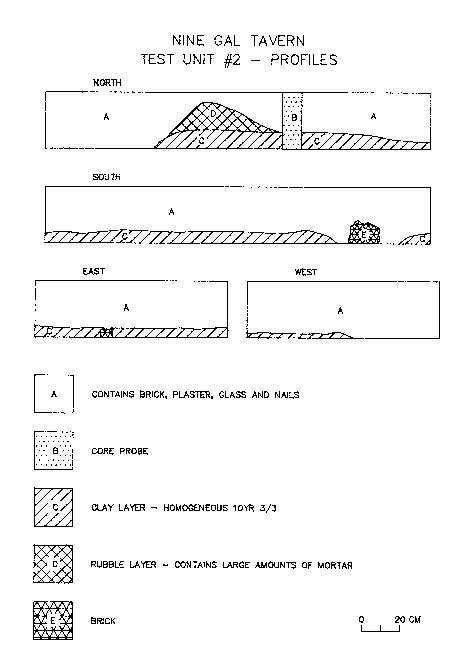

| Figure 3. Test Unit #2 of the Nine Gal Tavern Site. |

|

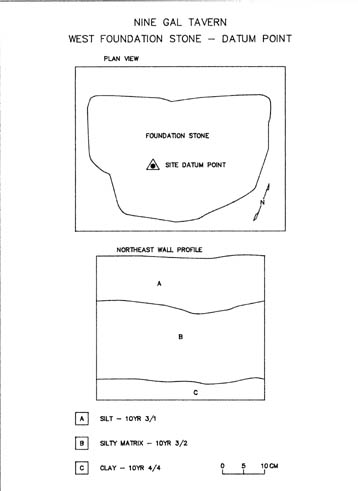

| Figure 4. Test Unit #3 of the Nine Gal Tavern Site. |

|

| Figure 5. Test Unit #4 of the Nine Gal Tavern Site. |

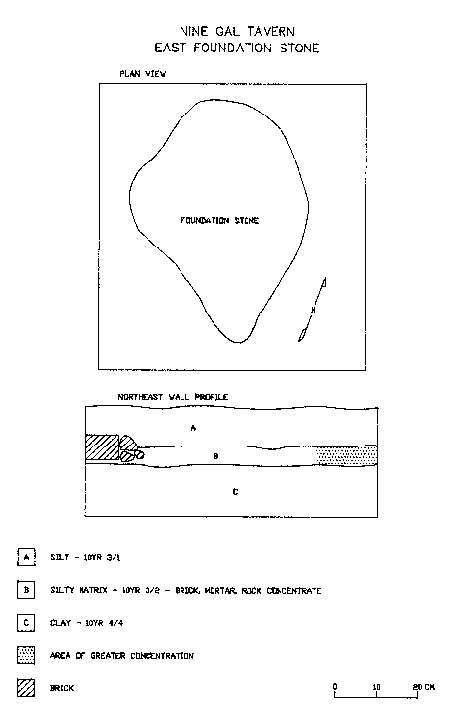

Figure 6. Feature #1 of the Nine Gal Tavern Site.

porcelain (1), bottle glass (1), flat glass (2), cut glass (1), pressed glass (2 objects, one of which was a fragment of a paneled tumbler), metal (12 items, notable of which were a hand wrought sprig, machine cut nails, a small spring, and part of a small pair of scissors), and early brick (2). Earthenwares were represented by redware (5), undecorated whiteware (6), hand painted polychrome whiteware (4), brown transfer printed whiteware (2), red transfer printed whiteware (6), and edge decorated whiteware (one item with a scalloped rim and impressed curved lines and one item with a scalloped rim and impressed bud designs). The mean ceramic date was 1844. The feature is interpreted as an ash pit associated with the fireplace on the east side of the Bryan structure. The deposition is from the Bryan occupation (1833-1853).

|

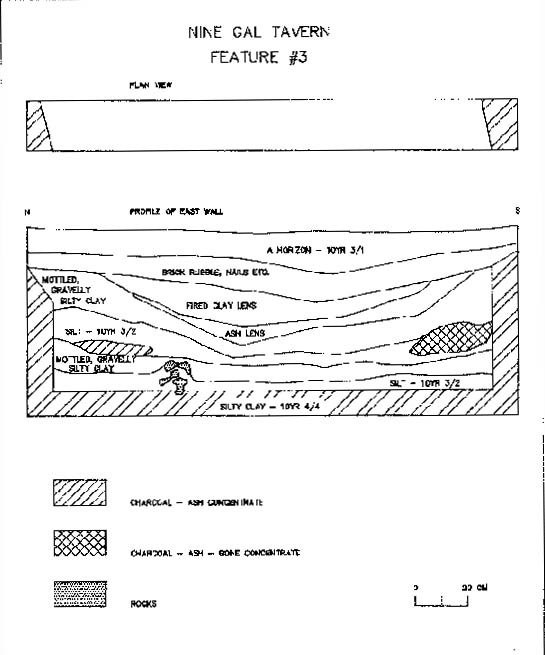

| Figure 7. Feature #3 of the Nine Gal Tavern Site. |

ceramic date is 1855. The bottle glass was represented by 37 items. Most of this was indeterminant except for color; although, there were two rough pontil bases. The pressed glass included five sherds, three of which were from paneled tumblers. The feature is interpreted as a trash pile associated with the Davidson occupation (1853-1856) and the operation of the Ohio Tavern.

2. Artifacts

A. Earthen Wares

Redware

Redware was a common recovery item (N=55), representing 6.8 percent of the

earthenwares. Table 1 indicates the distribution of redware by surface

treatment. The most common surface treatment was a lead glaze, of which 20%

was glazed only on the interior and 80% on both surfaces. The salt glazed

vessel had an unglazed interior. The two vessels with an Albany slip were so

treated on both surfaces. The base of a large mixing bowl had a white slip

interior and a clear glaze exterior. Much of the redware was recovered from

Features #1 (N=10) and #4 (N=13). Redware was produced in the United States

throughout the nineteenth century although its recovery may be more common on

sites predating the Civil War.

| Table 1. Redware Recovered From the Nine Gal Tavern Site. | ||

| Surface Treatment |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Unglazed |

3 |

5.5 |

| Lead Glaze |

15 |

27.3 |

| Salt Glaze |

1 |

1.8 |

| Albany slip |

2 |

3.6 |

| White slip interior clear glaze exterior |

1 |

1.8 |

| Indeterminant |

33 |

60 |

| TOTAL |

55 |

100 |

Yellowware

Three forms of surface decoration were identified: clear glaze, Rockingham, and mocha. There was no annular decorated yellowware other than the sherd of mocha. The mocha body sherd was the familiar dark brown. The Rockingham included a body sherd and a molded basal element. Table 2 provides the frequency of each form. Representing only 2.3 percent of the earthenwares, yellowware is an uncommon ceramic from this site. Because of its long period of production, yellowware is not a particularly sensitive temporal indicator, but could have been present from the beginning of the site's occupation.

Pearlware

Pearlware is the earliest table ware horizon for the site. Twenty four sherds, representing 3 percent of the earthenware, were recovered (see Tables 3 and 4). Objects with no obvious surface decoration were classified as undecorated. It is the most common recovery category and included elements of three cups.

| Table 2. Yellowware Recovered From The Nine Gal Tavern Site. | ||

| Type |

Frequency(%) |

Production Range |

| Clear glaze |

13(68.4) |

1830 to present |

| Rockingham |

2(10.5) |

1840 to 1900 |

| Mocha |

1(5.3) |

1840-1900 |

| Indeterminant |

3(15.8) |

|

| TOTAL |

19(100.0) |

|

| Table 3. Pearlwares Recovered From The Nine Gal Tavern Site (see Table 4 for shell edge treatments). | ||

| Type |

Frequency(%) |

Median Production Date |

| Undecorated |

17 (89.5) |

1805 |

| Blue hand painted |

1 (5.3) |

1800 |

| Polychrome hand painted |

1 (5.3) |

1800 |

| TOTAL | 19 (100) | |

Whiteware:

| Table 4. Edge Decorated Wares From The Nine Gal Tavern Site. | ||

| Type |

Frequency(%) |

Median Production Date |

| Pearlware (N=5) Scalloped rim |

||

| Impressed curved lines |

2 (13.3) |

1817 |

| Embossed patterns |

3 (20.0) |

1829 |

| Whiteware (N=10) Scalloped rim |

||

| Impressed curved lines |

5 (33.3) |

1817 |

| Impressed straight lines |

2 (13.3) |

1820 |

| Impressed bud |

1 (6.7) |

1823 |

| Unscalloped rim Unmolded |

2 (13.3) |

1879 |

| TOTAL | 15 (99.9) | |

| Table 5. Whitewares Recovered From The Nine Gal Tavern Site. | ||

| Type |

Frequency(%) |

Median Production Date |

| Undecorated, Plain |

270 (38.5) |

1860 |

| Annular |

10 (1.4) |

1850 |

| Blue hand painted |

13 (1.9) |

1850 |

| Polychrome, hand painted |

26 (3.7) |

1840 |

| Sponge/spatter ware |

16 (2.3) |

1850 |

| Transfer printed: |

|

|

| Blue |

29 (4.1) |

1845 |

| Black |

5 (0.7) |

1840 |

| Brown |

8 (1.1) |

1840 |

| Purple |

11 (1.6) |

1845 |

| Green |

19 (2.7) |

1840 |

| Red |

66 (9.4) |

1840 |

| Mid-blue |

16 (2.3) |

1829 |

| Polychrome |

6 (0.9) |

1850 |

| Flow Blue |

21 (3.0) |

1850 |

| Plain, embossed |

3 (0.4) |

1860 |

| Decalcomania |

3 (0.4) |

1930 |

| Luster |

2 (0.3) |

1870 |

| Indeterminant |

177 (25.3) |

1860 |

| TOTAL | 701 (100.0) |

|

B. Stoneware

| Table 6. Stoneware Recovered From The Nine Gal Tavern Site. | ||

| Type |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Unglazed |

8 |

7.7 |

| Salt glazed exterior Unglazed interior |

8 |

7.7 |

| Albany slip interior |

13 |

12.5 |

| Albany slip, both sides |

35 |

33.7 |

| Bristol |

1 |

1.0 |

| Blue and gray |

3 |

2.9 |

| Indeterminant |

18 |

17.3 |

| TOTAL |

104 |

100.1 |

C. Porcelain

D. Clay pipes

E. Bottle glass

| Table 7. Porcelain Table Wares Recovered From the Nine Gal Tavern Site. | ||

| Surface Treatment |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Plain white |

14 |

67 |

| Hand painted monochrome |

3 |

14 |

| Hand painted polychrome |

1 |

5 |

| Luster |

2 |

10 |

| Decal |

1 |

5 |

| TOTAL | 21 |

101 |

F. Pressed glass

| Table 8. Frequency Distribution of Construction Characteristics Identified on Bottle Glass Fragments From the Nine Gal Tavern Site. | ||

| Characteristic |

Frequency |

Production Range* |

| Molds: |

||

| Three piece |

1 |

1810-1880 |

| Two piece |

7 |

1845-1890 |

| Turn/Paste |

1 |

1880-1905 |

| Automatic bottling machine |

7 |

1903-present |

| Rough pontil |

7 |

1810-1860 |

| Snap case |

12 |

1855-1903 |

| 3/4 round base |

1 |

1900-1903 |

| Laid on lip ring |

1 |

to 1845 |

| Applied lip ring |

1 |

1850 - 1870 |

| Glass color black or opaque |

2 |

1815 - 1875 |

| Glass color purple |

3 |

1880 - 1918 |

| Glass color clear or aqua** |

131 |

to present |

| Pre-chilled iron mold |

2 |

to 1870 |

| Slug plate |

53 |

1850 - 1905 |

| Embossing |

11 |

1867 - 1905 |

| TOTAL | 238 |

|

|

* Adapted from Deiss (1981:92-96) and Newman (1970). ** Color was the only observable characteristic on the fragment. |

||

swirled patterns (9%), paneled or fluted patterns (23%), and plain (67%). Fluted tumblers were both hexagonal and octagonal. The other pressed table wares (N=24) included elements of sugar bowls, creamers, jars, plates, and bowls. Design features included ribbing, ray patterns, flower patterns, acid etching, and a single element of cut glass. The vast majority of this material was clear; although, blue, lavender, green, and amber were encountered.

H. Metal

| Table 9. Nail Types Recovered From the Nine Gal Tavern Site (after Nelson [1968]). | |||

| Nail Type |

Frequency |

Percent |

Production Range |

| Hand wrought |

6 |

0.7 |

19th century |

| Early machine cut hand made head |

4 |

0.4 |

1780-1820 |

| Completely machine cut sprigs and brads |

7 |

0.8 |

1805 - present |

| Early machine headed

cut nails |

400 |

43.6 |

1818 - 1840 |

| Modern machine cut nails |

256 |

27.9 |

1840 - present |

| Modern wire nails |

183 |

20.0 |

1850 - present |

| Unidentified |

61 |

6.7 |

|

| TOTAL |

917 |

100.1 |

|

internal combustion engine. Harness buckles and clips, as well as a horse shoe were also identified.

I. Structural materials

J. Other

Discussion and Implications

Pre-Tavern

Tavern Type I: Incidental Tavern

Gone is that free-hearted hospitality which made of every settler's cabin an inn where the belated and weary traveler found entertainment without money and without price.

1. Population density - Population densities of less than two people per square mile for township sized regions would have supported this stage. Platted villages were separated by more than a day's travel time. Walls (1989 personal communication) considers this to be extremely low and typical of the early pioneer period. Champaign County was formed in 1833. The Bryans homesteaded in 1834 and were the third family to do so in Middletown Township.

2. Transportation system - The transportation system consisted primarily of trails with few wagonable roads. However, it expanded exponentially during this stage as links to homesteads were carved across the landscape. Primary arteries like the Ft. Clark Trail were simply unimproved wagon roads. Poorly maintained, the main line of the trail moved laterally and sinuously during wet weather in response to the notorious "chug holes."

3. Demand - Economic demand was greatest at those homes located near the intersection of trails, river fords, or at daily conveyance distances along lines of travel. At these loci, sojourners had an interest in warm food, sleeping indoors, sociability, information, supplies, and equipment repair. To the extent that demand remained low and sporadic, travelers were simply fed and put up for the night.

4. Exchange - A reciprocal form of exchange generally obtained. It involved both social and material transfers. The social component could display varied elements. For instance, conversation and interaction with outsiders was both intrinsically rewarding and prestige granting. Secondly, the possessor of information from the world outside had the power to define and interpret that world to the local community. Thirdly, the distinction as the family with the building large enough or attractive enough to be chosen by the traveler provided an external source of social validation for the family's position within the community. Lastly, the demonstration of food surpluses adequate for use in economic exchange with the traveler affirmed prestige within the community.

5. Regulation - Attempts at regulation rarely extended beyond the weight of public opinion. Negative sanctions were informal and typically diffuse. However, in this stage unsanctioned groups of local citizens, vigilantes or "regulators", may have tried to control those individual proprietors who attempted to immorally exploit (theft, assault, and murder) the traveler (Wagner 1988).

6. Environing community - This level of tavern development demanded a local population capable of responding to the social transfers and rewards of the exchange system. We might best think of these communities as proto-communities, in that they were geographically diffuse. In the present context the community was locally labeled the "Sangamon Timber Settlement." The physical extent was from near the contemporary village of Fisher to the Piatt County line, a linear distance of twenty miles. It signified the region of early homesteading in western Champaign County. But in its definition, the geographic boundaries were in some ways less important than cultural boundaries. The residents evidenced homogeneity in their social attitudes, economic activity, religious orientation, and political interests (Walls 1989).

7. Material form - The material assemblage would be differentiated from that of a single family farmstead only in its relative wealth, complexity, and magnitude. The residential structure would be substantial by local standards. While early homesites were hewn of logs in this region, by the early 1830s sawed lumber was available and used with increasing frequency. The ceramic assemblage would center on expensive wares and might evidence considerable variation. While glass would be reasonably common, its incidence would be tempered by technological considerations and availability. One would expect to find both expensive and innovative forms (for instance, flint glass, cut glass, or early pressed glass). Liquor glass, both bottles and service, would be incidental to the assemblage.

Discussion: The Bryan occupation of the Nine Gal Tavern Site displays many of the characteristics of the Incidental Tavern. The family was the third such to homestead in the township. They were agriculturalists and never applied for a license to keep tavern. The large home they built was positioned near the intersection of the two major trails transecting the township and near the most important river ford. The homestead was located approximately a days journey west of the county seat and on the east side of the Sangamon. When the river was at flood, west bound travelers may have been stopped for more than a week waiting for the waters to recede. There were no alternative accommodations for travelers to access.

Tavern Type II: Incipient Tavern

| Table 10. Mean Ceramic Value of Features #1, #2, and #3. | |||

| Type |

Frequency |

1855 Value |

(f) x (Value) |

| Undecorated |

26 |

1.00 |

26.00 |

| Minimal |

14 |

1.16 |

16.24 |

| Hand painted |

14 |

1.3 |

18.20 |

| Transfer printed |

93 |

2.5 |

232.50 |

| TOTAL |

147 |

|

292.94 |

| Mean Ceramic Value =292.94/147=1.9927 | |||

1. Population density - Population densities for township sized areas would have been in the range of 2 to 5 people per square mile. The population density of Middletown Township in 1840 is estimated at 2.5 to 3 persons per square mile (Walls 1989:4).

2. Transportation - The transportation system continued to expand with wagon trails forging links to the increased number of homesteads. County and state government increased their response to the need for road improvements. In 1836, the Champaign County Commissioners authorized Isaac Busey and Jonathan Osborn to initiate a state road from Urbana to Bloomington. It followed the furrow plowed by Fielding Scott to the Sangamon ford the previous year (Purnell 1955:40). A differentiated political structure known in Champaign County as the Township Road Commissioner was created. Road taxes were legislated. The tax could be paid with labor rather than money. The Road Commissioner kept track of the number of hours of labor expended by each citizen.

3. Demand - Although demand for public accommodations increased during this stage, it was still not adequate for the initiation of a fully differentiated business activity. While more customers were on the road, the demand remained intermittent in response to such events as flooded rivers and roads or seasonal as in the market created by migratory farm labor. In a developmental context, when the homesteader felt the need to begin charging for services because of increased demand, signage might have occurred with the informal and generic "keep public" (Buley 1950:481).

4. Exchange - With increased demand, the drain on economic resources was too great for social transfers to provide sufficient reward for the local resident. Exchange became increasingly cash oriented. Signage functioned as a social device legitimating the charging of fees and the utilization of cash as the medium of exchange (Buley 1950:481). Larger local populations and increasing economic differentiation, as well as the need for income producing employment recast the circumstance of the traveler as a commercial opportunity. Exchange at this level followed the market principle; charges were such as the market would bear.

5. Regulation - County level government became involved in the regulation of services and pricing with a likely eye toward potential tax revenues and community image. By 1836 Champaign County had begun licensing taverns and regulating charges (Champaign County Commissioners' Record Book A). The licensing fee was $2.00 per year. The entry regarding the fee structure reads:

|

For keeping a man and a horse one night, including supper, bed and horse

feed..$0.75 For a single meal.................$0.18 3/4 For single horse feed..............0.12 1/2 For one-half pint whiskey......... 0.06 1/4 For one-half pint French Brandy....0.18 3/4 For one-half pint Wine.............0.18 3/4 For one- half pint Gin..............0.12 1/2 For one-half pint Rum..............0.18 3/4 For one half pint Domestic brandy..0.18 3/4 |

6. Environing community - The community which supported this stage placed increased emphasis on geo-political boundary definitions. Communities were platted and legal identities established. In Middletown Township commercial differentiation included such enterprises as ferries (1836), saw and grist mills (1837), blacksmiths, and retailing (1836) (Brink, McDonough and Co. 1878:125). In 1836 the village of Middletown was platted and the developer, Daniel Porter, opened a general store and tavern (both were licensed by the county [County Commissioners' Record Book A]). He also served as postmaster. Developers like Porter used these civil and commercial nuclei as magnets for residential populations, village growth, and long range profit from land sales.

7. Material form - The architectural expression that would characterize the Full Tavern surfaced at this stage. A large, two story frame structure was the style most frequently encountered in the study area. These buildings were rarely fabricated with the tavern function in mind; consequently, existing structures that displayed the appropriate design elements were exploited. Critical considerations included buildings that offered reasonably large public areas for food service and conviviality and multiple segregated areas for sleeping. The ceramic assemblage associated with the Incipient Tavern would be dominated by less expensive wares. There might also be an increase in the number of sets of dishes and durability would be an important consideration. Inexpensive glass, again conditioned by technological considerations and availability, would be more common than in the first stage. Liquor glass, both bottles for storage and sale and tumblers for service, would be common.

Discussion: The history of the Nine Gal Site provides no evidence of the Incipient Tavern stage. However, the form is seen in three other tavern sites known to the community: Porter's tavern (1836) in the platted village, the Mathew Johnson Tavern (by 1847), and the Rea Tavern or American House (1848). All three were ancillary economic activities for the proprietors: Porter was a developer and merchant undoubtedly using the tavern as a device for encouraging settlement and secondary to retailing, Johnson was a farmer whose residence was situated so as to make retailing and tavern keeping an opportunistic form of income, and Sarah Rea kept the American House Tavern in the family residence of the farmstead. What these particular sites would look like archeologically remains an unanswered empirical question.

Tavern Type III: Full Tavern

1. Population density - Population densities for a township sized region would be in the range of 5 to 8 people per square mile. Mahomet Township demonstrated a per square mile density of 6.9 persons in the 1850 census (Walls 1989:4). The presence of small villages was noticeable. Some of these were platted, others were not. These villages had residential populations of one to five families and were separated by less than a days travel time.

2. Transportation - The network connecting homesteads to villages and villages to villages underwent further expansion. The interest in the quality and maintenance of highway system continued unabated.

3. Demand - Public transportation in the form of the stage coach was significant to the emergence of this expression. As indicated previously, the stage stop guaranteed a regular and stable market of travelers seeking services. What changed relative to the Incipient Tavern was the volume of stage traffic and number of travelers. In Middletown Township it was this increased volume that enabled the Full Tavern. The increased size and economic complexity of the local community, as well as a sustained flow of travelers, facilitated the creation of multiple taverns. When this expansion of the industry occurred, some establishments worked with specialized markets like wagoner freight haulers, local workers, new arrivals, and stage coach travelers. Others concentrated their business on the local residents who were increasingly using the taverns as places of refreshment and libation. Taverns could now be stratified in terms of the quality and character of the service rendered (i.e., Abraham Lincoln is claimed by local historians to have stayed at the Ohio Tavern).

4. Exchange - Cash was the medium of exchange for this stage, and its production was the fundamental motive for the entrepreneurial activity. Proprietors of a Full Tavern relied upon the business as their primary source of income.

5. Regulation - Unfortunately, the Champaign County Commissioner's record book for this period has been irretrievably lost to water damage. Consequently, it is much more difficult to determine who was issued a license, if changes in fee structures were occurring, and how rigorously the requirements were being enforced. A likely scenario is that licenses were still required, but fee prescriptions for services other than lodging were largely abandoned, or, in the case of beverage alcohol, replaced by other forms of governmental regulation.

6. Environing community - The community which supported this tavern stage evidenced a significant increase in commercial diversification. The 1850 census listed 49 farmers and 92 farm laborers, a millwright, a grocer, two inn keepers, a physician, two merchants, four blacksmiths, three carpenters, and a laborer (Walls 1989:32). With the increased economic differentiation, an improved transportation system, an established system of public transportation, institutionalized religious groups (by 1858 there were three churches [Purnell 1955:42-45]), public school districts, and a greatly expanded residential population increasingly interested in leisure time consumptive practices, the frontier community was drawing to a close (Walls 1989). As indicated by the 1860 census, the range of occupational endeavors had increased from 10 to 28. The period from 1850 to 1860 witnessed exponential growth in the occupational infrastructure of the township.

7. Material form - The material assemblage of the Full Tavern would focus on a diversity of inexpensive, durable table wares (for instance, plain whiteware, ironstone, or hotel china), an increase in liquor glass, and an increase in pressed glass tumblers. Phillippe (1987) reports fluted, pressed glass tumblers as the most common glass category in the recovery from the Cox Tavern. One might also expect an increase in the frequency of chamber pots. The architectural style that emerged with the Incipient Tavern would continue. In Middletown Township, Full Taverns were located in buildings that had already functioned as taverns. A large, two story building with adequate area on the first floor for food preparation, serving areas, perhaps a bar, and small, private sleeping quarters on the second were typical. There were three Full Taverns operating within the Township during this period: the Ohio Tavern, the Nine Gal Tavern, and Dr. Adams' Hotel.

Discussion: The Nine Gal Site provides evidence of the Full Tavern stage. Both the Ohio Tavern and the Nine Gal Tavern fall into this category. From the exploration of the site, two discrete deposits were identified relating to these two occupations: Feature #4 to the Ohio Tavern and Feature #5 to the Nine Gal Tavern. Both features were dominated by plain whiteware. Table 11 contains the data bearing on the calculation of the mean ceramic value of Feature #4 and Table 12 of Feature #5. Note that there are significant differences in both the variety of ceramics (10 types for the Ohio to three types for the Nine Gal) and in their mean value (1.39 for the Ohio to 1.00 for the Nine Gal). A possible interpretation of these differences is that the Ohio Tavern, the one that Abraham Lincoln stayed at, was specializing in the higher status segment of the market. Bottle glass constitutes a much larger fraction of the total assemblage than was the case for the Bryan's Incidental Tavern. Additionally, there is also significant

| Table 11. Mean Ceramic Value of Feature #4. | |||

| Type |

Frequency |

1855 Value |

(f) x (Value) |

| Undecorated |

26 |

1.00 |

26.00 |

| Minimal |

3 |

1.16 |

3.48 |

| Hand painted |

2 |

1.3 |

2.60 |

| Transfer printed |

10 |

2.5 |

25.00 |

| TOTAL |

41 |

|

57.08 |

| Mean Ceramic Value = 57.08/41=1.3921 | |||

| Table 12. Mean Ceramic Value of Feature #5. | |||

| Type |

Frequency |

1855 Value |

(f) x (Value) |

| Undecorated |

95 |

1.00 |

95.00 |

| Minimal |

1 |

1.16 |

1.16 |

| Hand painted |

0 |

1.3 |

0.00 |

| Transfer printed |

0 |

2.5 |

0.00 |

| TOTAL |

96 |

|

96.16 |

| Mean Ceramic Value = 96.16/96=1.0016 | |||

variation between the Ohio Tavern component and the Nine Gal Tavern component with regard to the ratio of dishes to bottle glass. For the Ohio Tavern the ratio is 4.5:1 and for the Nine Gal Tavern the ratio is 2.3:1. Moreover, virtually all (94%) of the bottle glass from the Nine Gal Tavern feature was in the form of liquor bottles. The dispensing of liquor may have been a more important activity at the Nine Gal Tavern. Curiously, no pressed glass tumblers were identified from the Nine Gal feature and only five sherds were identified from the Ohio Tavern feature. Chamber pots were not recovered from either feature. In conclusion, and fully sensitive to the limits imposed by the size of the samples, the data suggests that the Ohio Tavern and the Nine Gal Tavern were directed at specialized segments of the local market.

Post-Tavern

Conclusion

REFERENCES CITED

- Abbott, Stephen C.

- 1902 The Autobiography of Stephen Conger Abbott.

Unpublished manuscript on file at the Champaign

County Early American Museum.

- 1985 1,000 Facts About Mahomet Published in the 'Mahomet Sucker State' Beginning Issue June 22, 1944. Manuscript on file Urbana Free Library. Urbana, Illinois.

- 1985 1,000 Facts About Mahomet Published in the 'Mahomet Sucker State' Beginning Issue June 22, 1944. Manuscript on file Urbana Free Library. Urbana, Illinois.

- The Breeder's Gazette

- 1911 May 31 no. 22. Methods of Successful Business Farming. Chicago, Illinois.

- Brink, McDonough and Company.

- 1878 History of Champaign County,

Illinois.

Philadelphia.

- Buley, R. Carlyle

- 1950 The Old Northwest Pioneer Period

1815-1840, Vol. 1. Indiana University Press. Bloomington, Indiana.

- Champaign County Gazette. Obituaries. 4 Feb 1880.

- Champaign County, Illinois.

- N. D. Champaign County Commissioners' Record Book A.

Manuscript on file in the Archives of the Urbana Free Library. Urbana,

Illinois.

- 1979 Recorder of Deeds. Deed Index: Grantor 1833-1927. Vol. A, B1. Manuscript on file in the Archives of the Urbana Free Library. Urbana, Illinois.

- 1979 Recorder of Deeds. Deed Index: Grantor 1833-1927. Vol. A, B1. Manuscript on file in the Archives of the Urbana Free Library. Urbana, Illinois.

- Cunningham, Joseph O.

- 1905 Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois

and History of Champaign County. 2 Vols.

Munsell Publishing Co.. Chicago, Illinois.

- Deiss, Ronald W.

- 1981 The Development And Application Of

A Chronology For American Glass. M.S.

Thesis. Illinois State University. Normal, Illinois.

- Lothrop, J. S.

- 1870 Champaign County Directory 1870 -

1871.

- Mathews, Milton W. and Lewis A. McLean.

- 1979 Early History and Pioneers of Champaign County. Unigraphic, Inc. Evansville, Indiana.

- McCorvie, Mary R.

- 1987 The Davis, Baldridge, And Huggins

Sites: Three Nineteenth Century Upland

South Farmsteads In Perry County,

Illinois. Preservation Series 4. American Resources Group, Ltd.

Carbondale, Illinois.

- McKearin, Helen and Kenneth M. Wilson

- 1978 American Bottles and Flasks. Crown

Publishers, Inc. New York.

- Morgan, Richard L.

- 1969 Cornsilk and Chaff of

Champaign County.

Sesquicentennial Committee of Champaign County.

Champaign, Il.

- Nelson, Lee H.

- 1968 Nail Chronology as an Aid to Dating Old Buildings. American Association

for State and Local History, Technical Leaflet No.48. History

News 24(11).

- Newman, T. Stell

- 1970 A Dating Key For Post-Eighteenth Century Bottles. Historical

Archaeology. 70-75.

- Pease, Thomas Calvin.

- 1925 The Story of Illinois. A. C.

McClurg and Co.

- Phillippe, Joseph Sidney

- 1987 Hutsonville on the Wabash: Excavation of a Nineteenth Century River Town.

In Donald B. Ball and Philip J. DiBlasi. Proceedings Of

The Symposium On Ohio Valley Urban

And Historic Archaeology, Vol. V. Department of

Anthropology, University of Louisville. Louisville, Kentucky.

- Purnell, Isabelle S.

- 1955 History of Mahomet, Mahomet Methodist

Church Centennial. Mahomet Methodist Church. Mahomet,

Illinois.

- Rockman, Diana D. and Nan A. Rothschild

- 1984 City Tavern, Country Tavern: An Analysis of Four Colonial Sites.

Historical Archaeology 18(2):112-121.

- Roehm, Frances.

- 1986 Champaign County, Illinois, 1850, A

Historical Overview. Urbana Free Library. Urbana, Il.

- State of Illinois, Archives Division.

- 1982 Public Domain Sales, Land Tract Record Listing.

(Champaign County), Vol.2. Springfield,

Illinois.

- Stelle, Lenville J.

- 1986 Cultural Resources Survey: An

Environmental Summary Of The Lake Of

The Woods. Sangama Archaeology. Mahomet, Illinois.

- 1989 An Archeological Guide to the Historical Artifacts of the Upper Sangamon Valley. Sangama Archaeology. Mahomet, Illinois.

- 1989 An Archeological Guide to the Historical Artifacts of the Upper Sangamon Valley. Sangama Archaeology. Mahomet, Illinois.

- Wagner, Mark J.

- 1988 The Old Landmark Tavern. Paper presented at the 1988 annual meeting of

the Illinois Archaeological Survey. Lewiston, Illinois.

- Walls, Gina Denise

- 1989 Demographic Reconstruction: Mahomet Township 1850, 1860 and 1880. Manuscript on file Department of Social Sciences, Parkland College. Champaign, Illinois.

Please forward any thoughts or comments to: lstelle@virtual.parkland.edu